I don’t mind embracing my age, so I’ll confess to watching The Daniel Boone TV show (1964–1970). I can even sing the theme song.

If you’re a youngster, you may have seen it on cable reruns: Boone as the all-around good guy and frontier hero, conducting surveys and expeditions around Boonesborough, running into both friendly and hostile Indians, before, during, and even after the Revolutionary War.

Of course, there’s the TV Boone and the historical one—the Boone who symbolized Virginia’s land policies more than he shaped them himself.

Multiple states claim Daniel Boone because of his travels across the frontier — Pennsylvania, where he was born; North Carolina, where he came of age; Kentucky, where he blazed the Wilderness Road and helped open the interior to settlers; and Missouri, where he lived out his final years.

Today, our focus is Kentucky: how Boone’s surveying and trail-blazing symbolized Virginia’s land policies, and how those policies paved the way for statehood in 1792.

The explanation begins in1609 when King James I granted the Virginia colony a charter that stretched “from sea to sea,” sweeping aside the French, the Spanish, and of course the Indigenous nations already here.

During the Revolution, Virginia organized Kentucky County (VA), and by the 1780s it was further divided into Fayette, Jefferson, and Lincoln Counties. Together these counties formed a distinct bloc that petitioned Congress for separation from Virginia again and again.

With over 70,000 settlers by 1790, Kentucky had the numbers and leverage to become a state in 1792 and added the counties of Nelson, Bourbon, Madison, Mercer, Mason, and Woodford. For comparison, Ohio didn’t qualify for statehood until 1802, and that was through an exception called The Enabling Act.

“Wasted Land”

The Virginians of 1790 often described Kentucky as “wasted land,” which is not a legal term. “Waste” in property law usually referred to land not in active agricultural use (unfenced, uncleared, unplowed). Colonists and early legislators often borrowed this language to justify dispossession.

Today, we can appreciate that just because the land wasn’t managed with European methods doesn’t mean it was not being managed at all. For centuries, Shawnee, Cherokee, Mingo, and other nations had hunted, farmed, and burned the forest here. They moved seasonally between river bottoms and uplands, and their claims overlapped, making Kentucky one of the most contested landscapes in eastern North America.

Virginia dismissed this history and parceled Kentucky out as if it were empty. This language laid the groundwork for legislation like Virginia’s Land Law of 1779, which opened “unpatented lands” in the Kentucky district to Revolutionary War veterans of the Virginia Line, through bounty warrants.

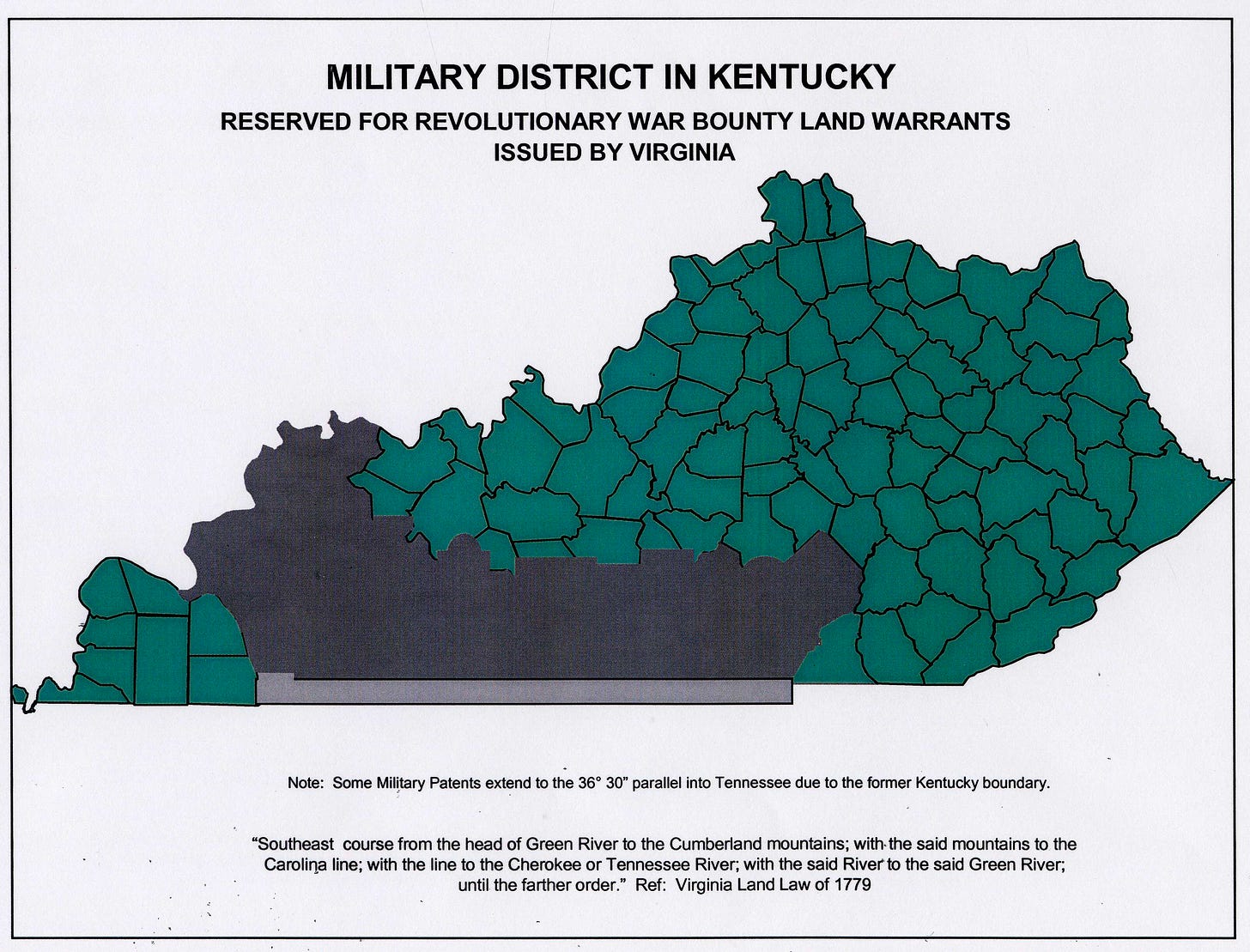

This swath of land is the Military District of Kentucky, shown in gray on the map below. Many veterans never came — selling their warrants to speculators — but the district shaped settlement patterns all the same.

The Land Law also legalized settlers’ preemption claims—squatters’ rights that gave anyone who had already built a cabin or cleared fields the first chance to buy land.

Encouraged by these policies, thousands funneled through the Cumberland Gap along Daniel Boone’s Wilderness Road, transforming the region within a generation.

The Dodgy Deal Behind Boone’s Road

Boone became the symbolic scout, but in reality he was on the payroll of the Transylvania Company, a massive speculative land venture of dubious legality.

In 1775 its founder, Richard Henderson, tried to buy twenty million acres directly from the Cherokee at Sycamore Shoals, paying with trade goods. Boone, then living in North Carolina, was hired to blaze the Wilderness Road and help build Fort Boonesborough to anchor the claim.

But the Royal Proclamation of 1763 forbade private purchases of Indian land, and both Virginia and North Carolina dismissed Henderson’s colony as a usurpation of their authority (the treaty at Sycamore Shoals took place on land that was then part of North Carolina).

Congress also refused to recognize it. Virginia eventually voided the purchase, though it granted Henderson and his partners 200,000 acres in Kentucky as a consolation prize, while North Carolina compensated them with land in present-day Tennessee.

It was an audacious bit of what people used to call “frontier lawyering”—an illegal land grab dressed up as a colony whose backers walked away with hundreds of thousands of acres. Henderson wasn’t just any dreamer and schemer—he was a North Carolina judge, with the connections and confidence to push further than most men would dare. And if the playbook looks familiar, that’s because versions of it are still making headlines today.

Transylvania collapsed as a colony, but Boone wasn’t a shareholder or speculator — he was the hired scout. When Virginia voided the Transylvania Company’s deal, Boone lost nothing personally, and his service was rewarded with land rather than reproach.

His association with Henderson’s speculative scheme faded in popular memory, leaving behind the heroic figure of Boone the pathfinder—a symbol of Kentucky’s opening, even if the machinery of land policy mattered far more than one man’s ax and rifle.

Metes and Bounds

Unlike Ohio, with its tidy federal grid of townships and ranges, Kentucky land was surveyed the old Virginian way: metes and bounds. A deed might run “from a white oak to a creek bend, then along the ridge to a large boulder.” This irregular system produced overlapping claims, and lawsuits that shaped county borders and political fights for generations.

The questions that follow will trace how these land policies—from Boone’s trail to the Military District—helped Kentucky emerge as America’s fifteenth state.

Note to my fantastic new subscribers:

It’s the rare person who can answer all ten trivia questions without any prep. I couldn’t answer them without a significant amount of research, either! Do your best and enjoy learning something new.

QUESTIONS

Answers in the footnotes. I’ll tell you if there is more than one correct answer.

1. Why did Virginians in the 1790s describe Kentucky as “wasted land?” Only one answer is correct.1

(a) It lacked mineral resources.

(b) They didn’t recognize Indigenous land use methods like seasonal migration, controlled burns, and unfenced fields.

(c) Because it was too remote to govern effectively from Richmond.

(d) Because Native peoples had already abandoned it.

2. Which Native nations actively used and claimed Kentucky, making it one of the most contested landscapes in eastern North America? More than one answer applies.2

(a) Shawnee

(b) Cherokee

(c) Mingo

(d) Iroquois (Haudenosaunee)

3. What was Kentucky County, Virginia, and how did it pave the way for statehood? One correct answer.3

(a) A single super-county created in 1776 that was later subdivided, forming a political bloc for separation.

(b) A military district organized solely for veterans.

(c) A western extension of Fincastle County, created to manage the frontier.

(d) A territory directly administered by Congress.

4. Why did Kentucky become a state in 1792 while northwestern Virginia counties had to wait until the Civil War to separate in 1863 (becoming West Virginia)? One correct answer.4

(a) Kentucky’s fertile farmland and central location drew migrants rapidly, giving it the numbers to press for statehood.

(b) Northwestern Virginia’s rugged mountains and poor transportation kept its population scattered and politically weak.

(c) Congress wanted to balance free and slave states, which helped Kentucky’s case.

(d) All of the above.

5. How did Virginia encourage migration into Kentucky? One correct answer.5

(a) By offering veterans bounty land warrants.

(b) By legalizing squatters’ “preemption claims.”

(c) By promoting migration through the Cumberland Gap and Boone’s Wilderness Road.

(d) All of the above.

6. Daniel Boone was celebrated as the heroic trailblazer of Kentucky, but in reality he was… One correct answer.6

(a) A contractor for the speculative Transylvania Company.

(b) A figurehead whose Wilderness Road became popular mainly because Virginia policy created courts, militias, and land offices on the other side.

(c) A wealthy land baron who accumulated thousands of acres and held them until his death.

(d) Both a and b.

7. Imagine you are a farmer in 1790s Kentucky. Your deed says your land runs “from a white oak tree to a bend in the creek, then along the ridge to a large boulder.” Your neighbor’s deed says nearly the same thing. What happens next under Virginia’s “metes and bounds” survey system? More than one answer is correct.7

(a) The two deeds overlap, and you end up in a lawsuit that could last for decades.

(b) The county court gets stronger, since everyone needs it to sort out overlapping claims.

(c) Speculators step in, buying up “disputed” land and reselling it to multiple buyers.

(d) The problem disappears once the federal survey grid reaches Kentucky.

8. Where was Kentucky’s Revolutionary War Military District located? One correct answer.8

(a) North of the Ohio River.

(b) South of the Green River in south-central Kentucky.

(c) Along the Cumberland Gap.

(d) In eastern Appalachia.

9. Why did many veterans never settle in the Kentucky Military District? One correct answer.9

(a) They sold their warrants to speculators.

(b) Some found the land too remote or already contested.

(c) Many preferred to remain in Virginia or move further west.

(d) All of the above.

10. How did Kentucky’s different settlement zones shape its antebellum identity? One correct answer.10

(a) The Bluegrass became a slaveholding plantation core.

(b) The Military District was a mix of small farms and speculative claims.

(c) The Appalachian east remained poor and isolated.

(d) All of the above.

Intermission

Here’s a list of pertinent books from our topic today:

Steven A. Channing, Kentucky: A Bicentennial History—concise, thematic overview.

Lowell H. Harrison & James C. Klotter, A New History of Kentucky—the standard survey.

Robert Morgan, Boone: A Biography—balanced, myth-busting Boone.

Here’s a Boone documentary by Kentucky’s PBS affiliate, KET. I couldn’t embed it here, so you’ll have to follow this link.

Want to get a jump on next month’s quiz? Read Steven Stoll, Ramp Hollow: The Ordeal of Appalachia — enclosure & the Appalachian commons. One of the most meaningful nonfiction books I’ve ever read.

ANSWERS

✅ (b) They didn’t recognize Indigenous land use methods

❌ (a), (c), (d) are plausible-sounding but wrong. Kentucky was fertile, not abandoned, and its “remoteness” didn’t stop Virginia from claiming and subdividing it.

“Waste” was a European legal fiction. Burning, shifting fields, and seasonal mobility were treated as non-ownership, which justified dispossession.

✅ (a) Shawnee, (b) Cherokee, (c) Mingo

❌ (d) Iroquois — they claimed sovereignty by treaty but did not occupy or hunt Kentucky in the same way.

Kentucky was overlapping, contested ground, not “empty.” This complexity made it a flashpoint of conflict throughout the 18th century.

✅ (a) Single super-county created in 1776, later subdivided

❌ (c) is the red herring—Kentucky’s story begins with Fincastle County, but by 1776 Virginia dissolved it—and out of its western portion came Kentucky County, the seed of the new state.

The rest of Fincastle County became Montgomery County and Washington County (both in southwest Virginia).

✅ (d) All of the above. Kentucky’s accessible farmland filled quickly; western Virginia was too rugged, isolated, and underpopulated to force separation until the Civil War.

✅ (d) All of the above. Land policy was deliberate: veterans were rewarded, squatters were legitimized, and the Wilderness Road became the funnel. Boone symbolized this system, but the state built it.

✅ (d) Both a and b

❌ (c) Boone as “land baron” is the myth. He lost most of his holdings due to debt and weak title claims. Boone’s fame far exceeded his actual political/economic power. He became the symbol of Virginia’s land policy more than its architect.

✅ (a), (b), (c)

❌ (d) is false — Kentucky never adopted the federal square survey. This messy system meant endless lawsuits, empowered county courts, and let speculators thrive. Kentucky’s patchwork of small counties is a direct legacy.

✅ (b) South of the Green River in south-central Kentucky. Known as the “South of Green River” reserve, it was set aside for Virginia Line veterans. The map shows this clearly.

✅ (d) All of the above. Most warrants were sold to speculators. Veterans often lacked means to move west or preferred land closer to home. The district was settled, but not by the men (yes, men) it was intended for.

✅ (d) All of the above. The Bluegrass became plantation-slavery country; the Military District mixed smallholders and speculation; the Appalachian east remained poor and isolated. These divisions foreshadowed Kentucky’s divided loyalties in the Civil War.