After the Civil War, industrial giants along the Ohio River—think Carnegie Steel, the railroads, and early electrical firms—began sponsoring baseball and football teams as part of a larger push to shape worker behavior, boost morale, and anchor company loyalty. Before jumping into the quiz, here’s some background.

Industrial Culture Loved “Manly” Sports

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, steel mills, coal mines, and railroad yards weren't just workplaces—they were gritty proving grounds for “real men.”

Baseball emphasized discipline, timing, and team cohesion—ideal traits for industrial workers.

Football, especially in its early brutal form, was framed as a crucible of toughness and hierarchy. Company executives loved it for “character building.”

The captains of industry (cough-cough) started “works teams” not simply as morale boosters, but also as tools of corporate paternalism, offered up alongside housing, clinics, and “recreation grounds” to reduce turnover and, conveniently, undermine union organizing. I wrote about this in the Kentucky coal fields on my website because my maternal family experienced Henry Ford’s “largesse”.

Some players held nominal jobs—night watchman, messenger, or other make-work titles—but were effectively paid to win, not to work. By the early 1900s, companies like Carnegie Steel were recruiting ringers and paying salaries that rivaled the minor leagues, all while claiming amateur status.

Teams like the Youngstown Ohio Works and Homestead Library & Athletic Club dominated regional leagues and occasionally squared off against professional clubs in exhibition games. The line between amateur sport and industrial propaganda? Let’s just say it was easy to blur when the scoreboard looked good.

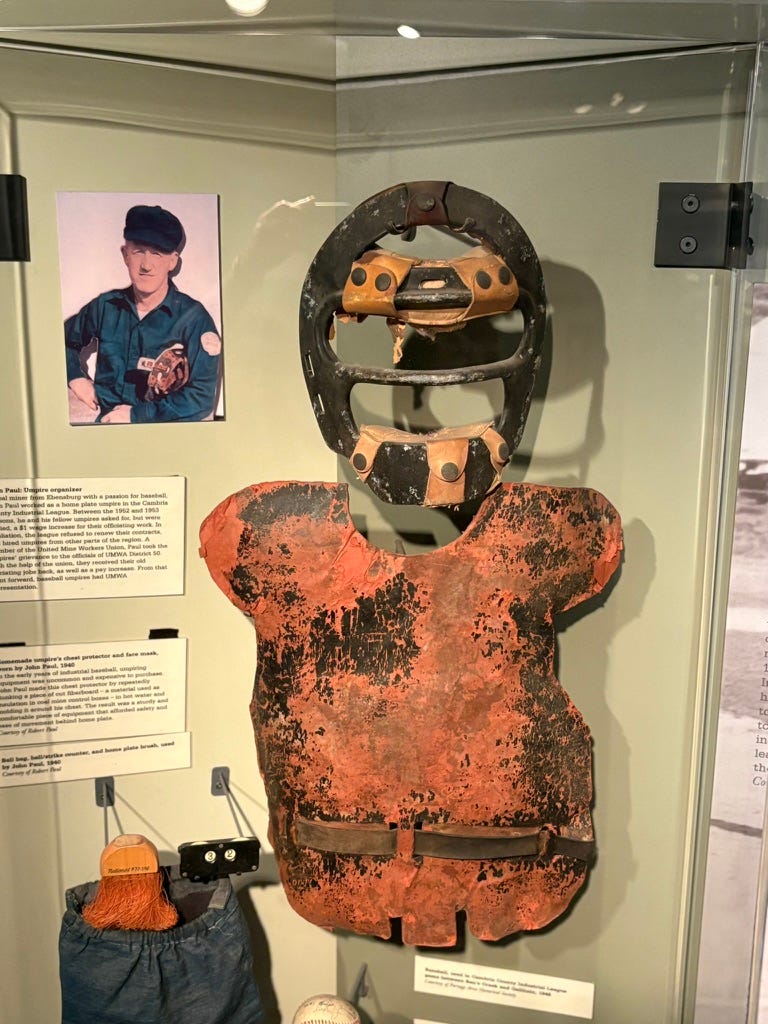

I was in Pittsburgh a couple of weeks ago at the Western Pennsylvania Sports Museum and will give you a longer story in a future newsletter.

When Works Teams Became Controversial

First get to know The Ohio–Pennsylvania League (O–P League)

Founded: 1905 and featured franchises based in Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia. The league was founded by Charlie Morton and operated for eight seasons, with the Akron Champs winning four league championships.

Level: The teams would be considered a Class C minor league by later standards, though such classifications weren’t fully formalized at the time.

Region: Mostly small-to-mid-sized industrial cities along the Ohio River and its tributaries—including Youngstown, Niles, Canton, Akron, and New Castle, PA.

In the 1905 Ohio–Pennsylvania League season, the Youngstown Ohio Works—sponsored by Carnegie Steel—drew sharp criticism for paying its players nearly double the league average, despite claiming to be “amateur.” Local newspapers fretted that the team’s salaries threatened the entire league's viability by forcing smaller-town clubs to overspend or fold.

To make matters wilder, a riot broke out during a game in Niles, Ohio, triggered by a fight among fans that escalated into dozens flooding the field and interfering with play, revealing how tightly corporate ambition, sport, and public spectacle intertwined.

Works teams weren’t just mascots of industrial generosity—they were flashpoints for debates about fair play, regional pride, and the limits of corporate influence in civic space. And when fans stormed the field, they showed that sport still belonged to the community—not just the company.

From Works Teams to the Big Leagues

As the 20th century unfolded, the scrappy industrial teams of the Ohio River Valley gave way to the polished machinery of professional leagues. No longer rooted in a specific mill or factory, teams began to represent entire cities—and their fans. With that shift came new forces: advertising, syndication, star players, and spectacle. Sports were no longer just tools of corporate morale or community cohesion. They became business.

The relationship between fans and teams evolved too. Where once the pitcher might’ve been your neighbor or coworker, now he lived in a nicer part of town—or maybe another city altogether. But the ties didn’t break—they morphed. Media coverage, mascots, and radio broadcasts helped forge a new kind of loyalty, more symbolic than social. The rise of mass media didn’t just change the game; it changed who the game was for.

Note to my fantastic new subscribers:

Monthly trivia is for sport. It’s not a test of intelligence or character. I had to do a significant amount of research before writing this. Do your best and enjoy learning something new.

QUESTIONS

Answers in the footnotes. Good luck.

Which of the following are true about the Homestead Library & Athletic Club football team near Pittsburgh in the early 1900s? Select all that apply.1

Its roster included multiple Ivy League All-Americans recruited by William Chase Temple with unusually high salaries.

The team emerged after the Homestead Steel strike of 1892, partly as a reputational salve. Critics later argued that its star-studded roster was a public distraction from the brutal union-busting that preceded it.

The payroll in 1901 was publicly disclosed at $25,000—an enormous sum that drew criticism as elitist spectacle.

Labor unions accused the athletic club of serving as distraction from the harsh conditions inside Carnegie’s steel mills.

Why did industrial companies in Ohio River towns sponsor baseball and football teams after the Civil War, but not sports like badminton or basketball?

Select all that apply.2A. Baseball and football aligned with masculine ideals prized by factory and mill culture.

B. Badminton and basketball were seen as leisure or indoor sports, more associated with schools and churches.

C. Outdoor team sports made better use of company-owned land and attracted large public crowds.

D. Basketball’s origins in Canadian-American YMCA culture made it less aligned with factory-floor values.

E. Football had a prestigious association with elite colleges, which company owners wanted to emulate.Which statements about early company-sponsored or community-supported sports in Ohio River towns are true? Select all that apply.3

A. Youngstown, OH, was known for company-backed baseball teams like the Ohio Works, which blurred the line between amateur play and professional recruitment.

B. Homestead, PA, supported powerhouse football teams backed by Carnegie-linked institutions, drawing national talent under the guise of amateurism.

C. Inspired by World War II-era efforts like the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League, many companies in the Ohio River region began sponsoring women's sports to support wartime morale and workplace equity.

D. Evansville, IN, had a robust boxing scene tied to its riverfront economy and immigrant labor population, though it wasn’t directly employer-sponsored.

E. Public athletic programs for women lagged behind men's, reflecting the gender norms of industrial paternalism and limited corporate investment in female recreation.Which of the following help explain how company-sponsored teams in Ohio River towns contributed to the rise of professional sports leagues in the U.S.?

Select all that apply.4A. Companies began recruiting elite college athletes, which normalized the idea of paying players for performance—even while claiming "amateur" status.

B. High-salary “works teams” created financial pressure on smaller clubs, accelerating the need for more formal league structures and revenue models.

C. Factory teams pioneered rule changes like designated hitters and shorter innings to boost productivity at work.

D. Local fan enthusiasm and press coverage helped build a media ecosystem that professional leagues would later rely on.

E. Some “company men” who managed teams (like William Chase Temple) went on to shape or own professional franchises.How did the rise of professional sports leagues in the early 20th century change the relationship between teams, fans, and media in Ohio River towns and beyond? Select all that apply.5

A. Games were increasingly covered by regional and national newspapers, helping transform local teams into entertainment brands.

B. Factory workers began traveling long distances to follow their favorite teams, sparking the earliest forms of organized sports tourism.

C. As professional teams replaced works teams, fans lost some of their personal connection to the players, who no longer worked or lived in the same communities.

D. Professionalization led to more women attending games, since the new stadiums were cleaner and marketed as family-friendly venues.

E. Local radio broadcasts in the 1920s and '30s created a shared experience across class and geography, reinforcing fan loyalty and team identity.Which of the following are true about the racial dynamics of early 20th-century works teams in Ohio River industrial towns? Select all that apply.6

A. Most company-sponsored teams were white-only, even in racially mixed workplaces.

B. Black athletes were sometimes invited to play if they could significantly improve the team’s performance.

C. Black workers often formed their own teams through churches or Black civic organizations.

D. Employers promoted Black participation in sports as a way to reduce racial tension in the workplace.

E. Segregation in company sports mirrored the broader exclusion of Black workers from upward mobility and social visibility in factory culture.Which of the following are true about Native American imagery in early 20th-century sports along the Ohio River and in its industrial towns? Select all that apply.7

A. Many industrial or semi-pro teams in Ohio River towns used Native American names to project strength, bravery, and “warrior spirit”—values prized by factory owners and fans alike.

B. Native-themed mascots were often introduced in towns where Indigenous communities still had a strong physical or political presence.

C. The rise of Native imagery in Ohio River Valley sports coincided with federal Indian assimilation policies, such as Indian boarding schools and cultural bans.

D. Teams often leaned into frontier myths, naming themselves after tribes who had historically lived—or fought—near the Ohio River.

E. These team names reinforced ideals of manhood and toughness that paralleled factory labor expectations in mill towns like Wheeling, Cincinnati, and Evansville.Which of the following are true about immigrant-sponsored sports teams in Ohio River towns during the industrial era? Select all that apply.8

A. Teams were often organized around specific ethnic groups, such as Polish, Irish, or Italian communities.

B. These teams played exclusively in private leagues and were banned from company-sponsored fields.

C. Ethnic leagues sometimes competed against company teams in informal exhibition games or town tournaments.

D. Some teams were sponsored by saloons, churches, or ethnic halls—serving as a point of pride for new arrivals.

E. Industrialists encouraged ethnic leagues as a way to foster multiculturalism and racial equity.How did “Blue Laws” affect early industrial sports culture in Ohio River towns?

Select all that apply.9A. Some towns prohibited games on Sundays, the only rest day for many workers.

B. Games played on Sundays were sometimes raided or fined by local authorities.

C. Blue Laws were most strictly enforced in Catholic-majority towns.

D. Labor unions and immigrant communities often pushed back against Blue Laws.

E. Some industrialists supported Blue Laws to limit unruly gatherings of workers.What role did railroads play in shaping company sports rivalries in the Ohio River Valley? Select all that apply.10

A. Teams from different towns used rail lines to compete in regional tournaments and exhibition games.

B. Some industrialists owned both railroad companies and sports teams, consolidating control of transportation and publicity.

C. “Rail Series” games were common—where towns along the same rail corridor played annual grudge matches.

D. Players were required to work on the railroad in the off-season to maintain amateur status.

E. Traveling teams helped spread company propaganda and brand loyalty to nearby towns.

Intermission

I found a video that claims to be the oldest video of a football game from 1903, when Princeton played Yale. Enjoy.

ANSWERS

✅ Correct answers: A, C, D. In other words, softening the narrative about brutal working conditions didn’t factor into the Homestead Library & Athletic Club football team

Homestead’s elite team in 1901 was bankrolled by Pirates co-owner William Temple and Carnegie executives, hiring top college talent for big pay packets. Its $25,000 payroll was a matter of public record, seen as part of a show‑boating recreational “perk” by industrialists—not grassroots community sports

While not often footnoted in union documents, the broader context of Homestead’s paternalist programs (like the Library & Athletic Club) laid over the same factory where workers later violently broke a union in 1892—labor critics saw these perks as symbolic pressure, not relief

✅ Correct answers: A, B, C, E

A. True, as discussed in the intro.

B. True — Basketball didn’t become a major commercial sport until much later. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it was played mainly in schools, YMCAs, and church gyms—not factory fields.

C. True — Large, open-air playing fields allowed entire neighborhoods to attend games, building team and town loyalty. Baseball diamonds and football fields were ideal for community cohesion—and for photos in the company newsletter.

D. False — Basketball was invented by Canadian-American James Naismith in 1891, but its delayed adoption had nothing to do with immigration or YMCA culture; it simply didn’t fit the corporate team model yet.

E. True — Football was associated with Ivy League prestige and institutional power. By recruiting star college athletes to their company teams, industrialists like William Temple (Homestead A.C.) borrowed elite credibility and cultural capital. Some things never change: sports have always been a way for wealthy men to flex. Think: Jerry Jones (Cowboys), Steve Cohen (Mets), and the Walton family (Broncos).

✅ Correct answers: A, B, D, E

C is false. It’s tempting to assume that the story behind A League of Their Own—women stepping onto baseball fields during World War II while men went off to war—represents a natural evolution of earlier corporate sports culture. But that’s a myth worth unspooling.

The All-American Girls Professional Baseball League (AAGPBL) wasn’t born from the same paternalistic playbook as the mill-town men’s leagues of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was launched in 1943 by chewing gum magnate Philip K. Wrigley, more as a publicity effort than a welfare program. The AAGPBL was about maintaining gate receipts and public interest. The players were not Wrigley employees in the chewing gum sense—they were athletes recruited and paid to play professionally, often under strict codes of femininity and conduct.

In contrast, earlier factory-sponsored sports were almost exclusively for men. Even into the 1930s, corporate investment in women’s athletics was minimal to nonexistent in industrial towns.

When women played sports in those regions, it was usually through YWCA leagues, church groups, or school programs—and almost never with employer pay, perks, or public attention.

And while Evansville, IN—an Ohio River town—was one of the league’s filming locations, the league itself didn’t field any teams in Ohio River cities.

Bottom line: A League of Their Own tells an important story—but it reflects a later wartime shift, not a natural outgrowth of company baseball along the Ohio River. That difference? It’s the gap between public spectacle and private paternalism, between cultural opportunity and institutional exclusion.

✅ Correct answers: A, B, D, E

C. False – There’s no evidence industrial teams altered the rules of the games for factory efficiency. If anything, they stuck to official rules to maintain legitimacy.

✅ Correct Answers: A, C, E

(B is plausible but not broadly true for this era; D has some truth but wasn’t a primary driver.)

A. True – Newspapers amplified team drama and star players, turning games into must-read stories and elevating teams beyond their town borders.

B. False (mostly) – While travel for championship games happened, regular sports tourism was limited by class and distance until much later.

C. True – When teams stopped being drawn from local factories, fans often lost that "one of us" feeling—making marketing and mascots more important for building loyalty.

D. Partially True – Some stadiums did become more hospitable over time, but professionalization didn’t immediately shift gender norms or marketing strategies; those changes came more slowly.

E. True – Radio broadcasts, especially in the Midwest, turned Sunday ballgames into household rituals, knitting together factory workers, housewives, and kids into fan communities across cities and towns.

✅ Correct answers: A, C, E

(B) Black athletes were sometimes invited to play if they could significantly improve the team’s performance happened on rare occasions in semi-pro baseball but wasn’t standard. (D) is false—corporate sports rarely addressed racial tension constructively.

✅ Correct Answers: A, C, D, E

A. True — Teams like the Portsmouth Red Birds (whose league featured several tribal-themed mascots) reflected a broader trend of using Indigenous identity as shorthand for aggressive play and manly grit—qualities industrialists promoted on and off the field.

B. False — By the early 1900s, few Ohio River towns had large Native populations. The use of tribal names was symbolic and romanticized, not reflective of present-day Indigenous presence.

C. True — The heyday of these mascots coincided with national efforts to assimilate Native Americans—boarding schools like Carlisle Indian Industrial School (in Pennsylvania) sent athletes to white colleges, even as tribal traditions were suppressed. See more about the Carlisle Indian Industrial School below.

D. True — Teams along the river often borrowed names from nearby historical tribes like the Shawnee, Mingo, or Miami—not to honor them, but to evoke frontier mythology.

E. True — In towns dominated by steel, coal, and rail, sports became a masculine proving ground. The mythic “Indian warrior” served as a symbolic stand-in for the kind of endurance and dominance the workplace demanded.

Carlisle Indian Industrial School’s football team gained national attention in the early 1900s by defeating powerhouse schools like Harvard, Army, and Yale. Its most famous athlete was Jim Thorpe (Sac and Fox Nation), widely considered one of the greatest athletes of the 20th century.

Carlisle football revolutionized the sport with trick plays and the forward pass—an innovation credited to Coach Pop Warner, who also coached at Pitt.

Graduates and athletes from Carlisle occasionally played in Ohio-Pennsylvania leagues, participated in exhibition games, or became coaches and role models in industrial towns across the Rust Belt.

✅ Correct answers: A, C, D

In places like Wheeling, WV, Newport, KY, and Youngstown, OH, immigrant communities often built their own parallel institutions—including baseball teams—that reflected their heritage and neighborhood loyalties. These teams weren’t always welcome in company-sponsored leagues, but they occasionally played cross-town exhibitions, especially on holidays. Ethnic pride, not integration, was the animating force—and industrialists were generally more interested in control than multicultural celebration.

✅ Correct answers: A, B, D, E

In places like Steubenville, OH and Evansville, IN, Blue Laws restricted Sunday recreation—including sports. This was controversial because Sundays were the only day most workers were off. Company teams often played on Saturdays, but ethnic and independent teams preferred Sundays, creating cultural friction. Labor groups sometimes aligned with immigrant advocates to oppose these laws. Meanwhile, conservative industrialists occasionally supported them—not just for religious reasons, but to avoid large, unsupervised gatherings of workers that could turn political.

✅ Correct answers: A, B, C, E

The interconnected geography of the Ohio River and its tributary rail lines made it easy for teams from towns like Ironton, OH; Wheeling, WV; and New Castle, PA to compete.

Rail travel allowed for multi-town leagues, and companies often paid for travel to enhance their corporate image. Some owners—like those in the steel and rail sectors—used teams to spread their company identity across town lines.

The “Rail Series” wasn’t always official, but informal rivalries (like those between neighboring river towns with direct rail links) became part of regional lore.