West Virginia's Palace of Gold

Yep, Appalachia had the first American Hare Krishna ashram

Everybody is looking for KRISHNA.

Some don't realize that they are, but they are. ~George Harrison (former Beatle)

I primarily remember the Hare Krishna movement of the 1960s and ‘70’s because it pushed the buttons of so many adults—adults who had no problem with the equally ecstatic so-called “Jesus Freaks”of the day.

I grew up about thirty miles east of Columbus, Ohio, and I don’t remember seeing any Hare Krishnas there, but I remember seeing a group at Port Columbus Airport when we waited for my grandparents’ plane to land from California. About a dozen shaven-headed, bare-chested, young white men banged tambourines and chanted Hare Krishna, Hare Krishna…at the arrivals area. My parents scooted us kids out of their way, and while I don’t recall their exact words, their warnings would have matched what I heard everywhere else about the counterculture movement, hippies, LSD, brainwashing, and cults: STAY CLEAR.

Fifty years later, I learned that the first American ashram (religious retreat) was built 150 miles due east of Columbus, just across the Ohio River near Moundsville, West Virginia. Back in the day, we would have called it a commune.

The first swami

In 1965, A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, an Indian man from Bombay, made a 12,000-mile ocean voyage to New York City hoping to bring Krishna Consciousness to the West, preaching a monotheistic version of Hinduism. By 1967, his movement was well underway, and two of his disciples decamped to West Virginia on a mission to start an ashram just outside of Moundsville. The property, New Vrindaban, is named after the holy land of Vrindavan, India, the place of Krishna’s birth.

On May 31, 1967, Prabhupada suffered a stroke and returned to India to recuperate. While recovering, he desired to establish a place in India for his foreign disciples to be trained. He planned to call it the American House; sometimes he called it the Indian-American House. He returned to America in December, 1967 to continue the expansion of Krishna consciousness. Then in 1970, he acquired the Los Angeles temple, which became the world headquarters of his ministry.

That same year, New Vrindaban in West Virginia held its first annual three-day celebration of Krishna’s birth. Hundreds of devotees from as far away as Australia are reported to have attended. By 1985, it’s said that 600 people lived and worked at New Vrindaban’s temple, schools, dairy, and Palace of Gold. At its peak, 250,000 tourists visited each year.

Visiting the ashram

My dear friend and longtime traveling companion, Jill, traveled with me to New Vrindaban by motorcycle in 2021. Do yourself a favor and click this link for pictures and explanations of what you’ll see. Here’s my account.

If you’re considering an overnight visit, you’ll be welcomed to book lodging there, with no obligation to attend services or eat meals at the ashram. Jill and I did both.

Checking in at dinnertime, we ate vegetarian dishes from a buffet in the dining hall off the temple, where we later watched a woman’s initiation into a holy order. The temple offers several services each day, and sometimes we saw various rituals taking place simultaneously at the various altars around the perimeter.

Our affordable lodgings reminded me of a college dorm room—plain, clean, and serviceable. Most of the other weekend visitors seemed to be ethnically South Asian. Fellow visitors and staff were gracious and open to our questions, and we fell asleep with the haunting cries of the ashram’s roaming peacocks punctuating the stillness.

The Palace of Gold

The next morning, we took a tour of Prabhupada’s Palace of Gold, which was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2019. Constructed over a period of years by volunteers with no architectural plans, the local believers intended the palace to be Swami Prabhupada’s retirement home. While he visited the palace seven times, he returned to India to continue his work, then passed away in 1977 at the age of 81.

While we waited for our tour of the palace itself, we lingered in the tranquil rose garden adjacent to the palace and beside the nearby lotus pond, where giant bullfrogs leaped and serenaded. At our appointed time, we doffed our shoes to enter the palace itself, which sits beneath a thirty-ton main dome with a 4,200-piece crystal ceiling. They imported the marble and onyx flooring from Europe, Asia, and Africa. While murals and other works of art cover ceilings and walls, 31 stained glass windows are reflected in crystal chandeliers. We could not take pictures inside, so you’ll have to take my word for its ostentation, which rivals that of Europe’s Baroque cathedrals.

Why couldn’t they keep it up?

Except for the temple itself, which is earnestly and continuously attended, the rest of the property was in a state of genteel decay: a bucket under a leaking ceiling here, rotted wood and blistered paint there. Sadly, whatever money and labor had built and maintained New Vrindaban to its height in the 1980s no longer flowed. Why couldn’t they keep it up?

Jill and I opted out of dinner at the ashram on the second night and rode our motorcycles down the ridge to Grandma Jo’s Polkadot Cafe in Moundsville. Our waiter had the fuller story of New Vrindaban, claiming that the community was a viper pit from its start. Now, I wasn’t surprised by that remark because Americans in general can be pretty intolerant of non-Western religions. But then he started giving details so awful that I just knew they had overblown. He said the ashram’s leaders had engaged in sexual predation of children and adults; that financial crimes (including arson) had funded their operations; and its most powerful temple leader had ordered an assassination on dissidents during the late ‘70s and early ‘80s. WHAT?

Sadly, the public record backs the waiter’s story. Turns out, the ashram’s lavish buildings had been funded not by pilgrims or tithing, but by 10 million dollars in illegal fundraising schemes, including the sale of caps and bumper stickers bearing fraudulent copyright and trademark logos. A co-founder of New Vrindaban was found guilty of racketeering in August 1996. His crimes included conspiracy to murder.

My heart sank to learn about yet another religion that can’t police itself. I had my answer to New Vrindaban’s descent. I can only imagine the difficulty of raising money and volunteers under clouds of so much criminality that runs counter to the movement’s peaceful teachings.

I respect the true believers who work like Sisyphus each day to greet the visitors, weed the gardens, milk the cows, repair the roofs, and adorn the temple gods with fresh flowers. I would find it painful to continue living and working there in the wake of so much harm and deceit. Their faith is stronger than most.

Hare Krishna in the wider culture

In the two years since leaving New Vrindaban, I’ve noted the ways the Hare Krishna movement showed up in my life, and continues to do so.

The Hare Krishnas made such an impact on the common culture that Hanna-Barbera (who gave us Scooby Doo) produced a 1973 episode of Wait Till Your Father Gets Home to lampoon the movement. The daughter, Alice, joins a commune so she learn how to farm and “get back to nature.” By the end of the episode, we learn a swami impersonator runs the commune so he can build a radish fortune on exploited labor. A radish fortune!

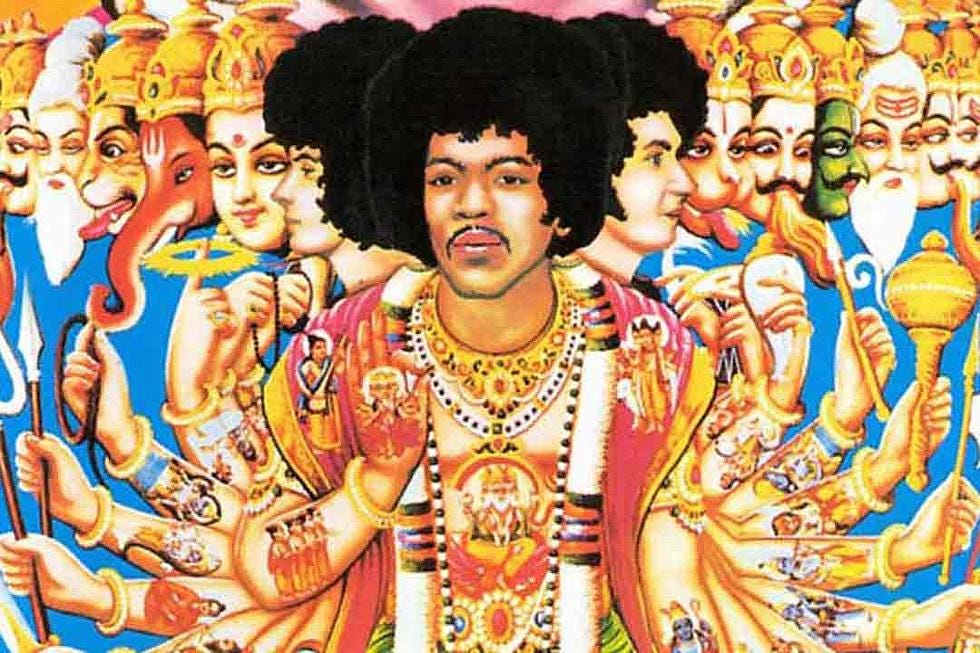

By 1967 Jimi Hendrix’s second album was released with an appropriated version of a Hindu devotional painting and I remember seeing posters and t-shirts in this unique style.

By 1969 the movement had reached and spread through the Beatles.

George Harrison produced a hit single, The Hare Krishna Mantra, one of five songs to his credit that mention Krishna, the most famous of which being My Sweet Lord.

John Lennon and Yoko Ono recorded Give Peace a Chance in their room at Montreal’s Queen Elizabeth Hotel, surrounded by Hare Krishnas and various celebrities who sang along.

The words "Hare Krishna" are included in Lennon's I Am the Walrus, and the background vocals of Ringo Starr's 1971 hit It Don't Come Easy.

Then of course there’s yoga, which I practice several times a week. Here’s a fascinating history of yoga in America. In 1893, a Hindu monk spoke of it at an interfaith conference held during the massive World's Columbian Exposition. His version of yoga did not include the flowing sequences of the asanas or postures we practice today in YMCA classes and private yoga studios. Nevertheless, he paved the way for the 1920s and ‘30s, when Hatha yoga made its way to the West. Seeing the Beatles in lotus position and then the lovely Ali McGraw on VHS teaching us asanas and breathing techniques had to figure into the growth of what is today a $9 billion industry in the U.S. alone, with more than 40,500 yoga and pilates studios here.

How about the common use of the Sanskrit word “mantra?” It’s supposed to mean “a sacred utterance” but it seems to only have caught on in the worst kind of business-speak.“, as in, My mantra is buy low, sell high.”

I loved chanting the 16-word Hare Krishna mantra at the temple in West Virginia with devotees and found it to be hypnotic and uplifting.

Hare Krishna, Hare Krishna,

Krishna Krishna, Hare Hare

Hare Rama, Hare Rama,

Rama Rama, Hare Hare

Here’s Krishna Das leading the mantra in call-and-response. If you’re a fellow oldster, you might recognize him from his Blue Oyster Cult days as Jeff Kagel.

Okay, there’s a lot here to unpack. What do you remember from the sixties and seventies? Did you ever encounter the Hare Krishnas? Ever visit the Palace of Gold? Did a religion ever test your faith?