Who Owns the Ohio River?

An esoteric question? Does it matter?

No man ever steps in the same river twice. For it's not the same river and he's not the same man. ~Heraclitus

Heraclitus’ famous quote is philosophically inclined, but I thought of it recently when telling a friend about a legal case between Ohio and Kentucky concerning, of all things, a boulder removed from the river.

Okay, when I put it that way, it sounds ridiculous (albeit true). It’s a little writerly device to keep you reading!

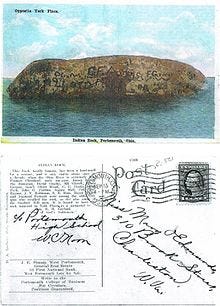

Indian Head Rock

Known as Indian Head Rock or Indian Rock, geologists think the boulder in question rolled into the river from the Kentucky hills of sandstone before the 19th Century. Someone carved what we would call a smiley face on the rock before pioneers discovered it and attributed the face to an Indian, hence the name.

Back before locks and dams, locals used the boulder to gauge the water level—by how many inches they could see over the eyes, the nose, or the mouth. The first record in the log was dated November 10, 1839, when the mouth of the figure was said to be “10 1/4 inches out of the water1.’” Boys being boys, several initials were added over the years, too.

Indian Head Rock was permanently submerged around 1917 when the Ohio River Lock and Dam No. 31 was finished, although it made a brief appearance in 1920 when No. 31 suffered damage. The Portsmouth Daily Times reported that "Hundreds of Portsmouth people Sunday took advantage of an opportunity to view the famous Indian Rock, which is located just across from the old [Portsmouth] waterworks plant. Many pictures of it were taken from all angles Sunday.2"

Did people forget about the boulder after 1920? Apparently, its memory was kept alive because an amateur historian set out to find it some eighty years later. Steve Shaffer assembled a team of divers and eventually located and photographed Indian Head Rock in 2002. By 2007, he and his crew successfully lifted the boulder from the riverbed and floated it to Portsmouth’s shore where a cheering crowd of locals waited. Shaffer made a pretty speech about Portsmouth's future generations once again being able to see the rock themselves and planned to place it on public display.3 Why in Portsmouth? The smiley face was seen from the Portsmouth side, so the locals presumably felt more sentimental about it.

Possession and the Law

All the fanfare about the boulder’s removal stirred up possessive sentiments in Kentucky. The Kentucky Native American Heritage Council, passed a resolution on November 1, 2007, calling for the return of Indian Head Rock to its original location—Ohio River bottom. Then a Greenup County (KY)grand jury issued an indictment against Shaffer for violating Kentucky's Antiquity Act. The University of Kentucky protected it as an archaeological object in 1986.

Eventually both the Ohio and Kentucky legislators got involved in the dispute until finally (cut to the chase) Kentucky got Indian Head Rock back by virtue of its original position on its side of the Ohio River.

Folks, there are lots of serious aspects to this funny little story, as its documentary film will show you. All of them involve doing what’s right on principle more than the inherent value of a sandstone boulder with (supposedly) ancient markings.

The Ohio River is an Exception to River Boundary Rules

Where a river separates two states, the legal boundary line is usually in the middle of the river. But not when it comes to the Ohio.

Before the U.S. gained independence from its colonial overlords and before the Articles of Confederation, a good deal of the Midwest was claimed by the sovereign and independent states of Virginia, New York, Connecticut, and Massachusetts4. Virginia laid claim to land on both sides of the Ohio River from the headwaters to the Mississippi.

In 1784, the Continental Congress laid claim to Virginia’s claims north and west of the Ohio River. However, the Ohio River itself remained outside of the bargain—Virginia owned it. When Kentucky became a state in 1792, ownership transferred from Virginia along with the land.

When Ohio became a state in 1803, it sought greater control appealing to the U.S. Supreme Court to shift the boundary line to the middle of the river. The Court, however, ruled that because Virginia had owned the Ohio River originally, it should remain a part of Virginia’s domain i.e. Kentucky. By that precedent, when Virginia lost its westernmost counties to the new state of West Virginia in 1863, the river boundary went with West Virginia. The low-water mark on the western bank of the Ohio River is still the western boundary of West Virginia.

In 1820, when Indiana became a state, the Supreme Court rejected Indiana's argument of taking ownership of the river from the middle.5 The Hoosier state tried again in 1890, arguing over Green River Island between Evansville, Indiana, and Henderson, Kentucky. Rivers change their course as is their nature. Little channels silt up or wash away with floods and erosion. Green Island is physically yattached to Indiana; it only appeared to be an island when the original boundary was drawn. But thanks to the Supreme Court, Green Island is still in Kentucky.

While civic pride plays some role in boundary matters, as we saw with Indian Head Rock, the real issue is money: revenue from fishing, boating, liquor, and other licenses granted for use on any portion of the river. Follow the Money!

Should the Borders Change?

In a day when we use satellite technologies for everything, it seems quaint that original surveying techniques sometimes relied on transitory objects like the white oak post marking a boundary in the West Virginia Northern Panhandle. We still rely on old boundaries, and as we see with Indian Rock, state legislatures are loathed to cede anything to another, especially when the monies that go with the land are significant.

Here’s a quote from a story by public radio station WVXU that explains it better than I could summarize.

(In) 1966…(Ohio )…wanted the border to be whereever the low water mark was.

(University of Cincinnati's) Brad Mank says that challenge bounced around the courts for a few years. A special master assigned to the case rejected Ohio's argument saying it was difficult to determine where the 1792 boundary was, but it wasn't impossible.

Finally in 1980, the case wound up in the Supreme Court. Mank says the three dissenting justices argued that the border should change as the river changes. Which is what happens with the Mississippi and Missouri rivers.

"But for the Ohio River, because it's based on what Virginia gave up in 1784 and 1792, it's all based on the historical boundaries and not where the river is," Mank says. "It seems awfully inconvenient, but that's what the Supreme Court said."

That's why the signs welcoming visitors to Kentucky are close to the Ohio side on bridges. It's also why Kentucky is responsible for those bridges.6

I hope this helps you win your next trivia contest!

"Would Preserve The Historic Indian Rock". Portsmouth Daily Times. October 8, 1908

Many Pictures Taken of Indian Rock". Portsmouth Daily Times. October 25, 1920.

"Group works to raise historic Indian's Head Rock from river". Herald-dispatch.com.

Ever wonder where Case Western Reserve University got its strange name? It’s because that part of Ohio (near Cleveland) was once the Western Reserve of Connecticut.

https://www.wvxu.org/local-news/2021-04-21/oki-wanna-know-why-does-kentucky-own-the-ohio-river

https://www.wvxu.org/local-news/2021-04-21/oki-wanna-know-why-does-kentucky-own-the-ohio-river

I always wondered about the state border between Huntington West Virginia and Chesapeake Ohio on the Ohio river. In my boyhood age (years before google and 1999) I just assumed the river was divided in half. I was wrong.

Headlines in those days were that the Chesapeake, Ohio police department hooked a body floating down the river within 10 feet of the Ohio rescuers standing on their Ohio shore. West Virginia said, no. Don't do it, that is our body. West Virginia sent ambulances, fire trucks, and everything else (mutual aid?) to recover the body that was laying in Ohio. It was gross.