When I visited Evansville, Indiana, on a bright summer day in 2021, its revived waterfront and fabulous murals captivated me. Since then, I delved into Timothy Egan’s book about the Midwestern Klan, where I discovered that Evansville was a hotbed for KKK activity in the 1920s. Unlike the Klan that terrorized the South during Reconstruction, its second wave looked beyond Blacks to hate and harass. It was nativist, focused on driving out Catholics and first-generation immigrants, as well as Jews—together with Blacks they’d always targeted, they manufactured a much wider target for hate.

It’s important to note that Blacks had been unwelcome in Indiana since its first Constitution specified, “No negro or mulatto shall come into, or settle in the State, after the adoption of this Constitution.”1 Intrigued by Indiana’s history of trying to maintain a WASP state (White Anglo-Saxon Protestant), I decided the Evansville African American Museum would be a vital stop.

The museum sits in a neighborhood that’s been called Baptisttown since the 1800s, in a building dating back to Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal Era. Constructed in 1938, it narrowly avoided demolition in the 1990s and opened as a cultural institution in 2007. Its story as compelling as those it narrates.

Evansville in the New Deal Era

By the turn of the (last) century, 54 percent of Evansville’s Black citizens lived in Baptisstown, and by WWI, the neighborhood became overcrowded to where a third of its residents had no access to sewage systems. Think for one second how miserable that must have been on a hot summer’s day (any day for that matter).

Racial segregation in Evansville was of course rooted in Indiana’s Constitutional “Black Laws” but it was later exacerbated by racial restrictive covenants known as “deed restrictions” banning Blacks from living or owning property in most parts of the city. The use of deed restrictions were widespread throughout the country, with more cities adopting them than not. Although the Supreme Court ruled the covenants unenforceable in 1948, it took the Fair Housing Act of 1968 to outlaw them.

But Indiana’s segregation predated deed restrictions. By the time the federal Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) analyzed Evansville neighborhoods in 1937, segregation was well-entrenched: 90% of Evansville's Black population lived in one of four neighborhoods. The HOLC outlined those four neighborhoods in red on the maps that they provided to lenders and insurance companies to use in deciding whether to do business in an area. Most companies avoided “redlined” neighborhoods, but if they did business there, it would be at a higher interest rate or insurance premium than offered elsewhere.2

As I hinted earlier, FDR’s Public Works Administration (PWA) tried to ameliorate the nation’s Depression-induced housing crisis by building 51 projects in 31 cities (seven were in Ohio River cities, including Evansville).3 The PWA was not focused on desegregation. It followed a “neighborhood composition rule,” meaning PWA housing projects should reflect the previous racial composition of their neighborhoods. Legal scholars note that this violated African Americans’ constitutional rights,4 but that was a battle for another day. To Evansville’s credit, local leaders resisted efforts to place the housing project outside the city limits, or to use the PWA to clear the neighborhood for white residents, as had happened in PWA communities elsewhere, despite the guidelines.

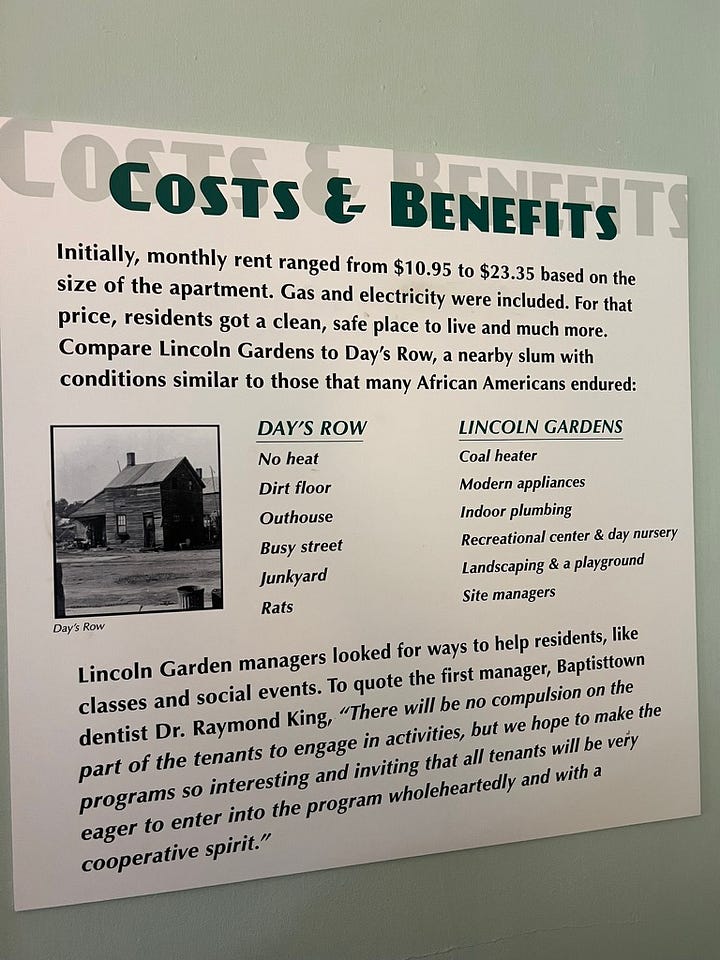

Evansville is in the heart of Lincoln Country, so the community’s name, Lincoln Gardens, resonated. For about $1m, Lincoln Gardens housed roughly 500 residents in 16 buildings of 182 low-cost apartments. It was the second PWA community to be built in the country.

First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt brought a touch of celebrity to Lincoln Gardens when she visited Baptisttown in November, 1937. Here’s an excerpt from her “My Day” newspaper column:

First we went to lay a wreath on the tomb of Private Gresham, who was the first solider killed overseas during the World War. Then to look at the slum clearance project in the colored section of the City, which is evidently a matter of great pride to the Mayor. He is very happy that this undesirable section from the point of view of housing, has been wiped out. He told me that the new houses would rent at approximately the same amount per room as the old ones which had been extremely high considering what they were. That is one point in any slum clearance project which has to be watched, for there is no use in providing new housing at a cost beyond the incomes of the former residents of the neighborhood.

As much as I love Eleanor, her fusty descriptions are cringy.

Visiting the Museum

On a balmy late-April morning, Ms. Janice Hale took me for a personal tour of the museum. She had lived in Lincoln Gardens with her mother and sister in the sixties, so her memories and reflections resonated deeply. She went on to a career in the Evansville Housing Authority at Lincoln Gardens, and has volunteered at the museum since her retirement more than a decade ago. Every community organization should be so blessed with the institutional and cultural memory that she brings to her work in Evansville.

The museum retains its shape as a brick apartment building, but with the addition of a semi-circular portico held up by columns shaped to resemble the baobab tree, native to Africa. Ms. Hale emphasized the tree's African mythology that says the ancestors' spirits are stored in its trunks, giving it the nickname, “the tree of life.” This picture of the building from the architect’s website is better than mine.

Stepping inside the two-story gallery space, it was easy to figure out the original placement of the first- and second-floor apartment units. The museum preserved a one-bedroom apartment on the first floor using period furnishings. In the bedroom pictured below, the curators placed a marriage certificate on the wall above the rocking chair because cohabitation by unmarried couples in Lincoln Gardens was forbidden (that prohibition is illegal today). Its kitchen includes a gas-powered refrigerator that was standard issue for each original apartment (pictured bottom-right below and manufactured in Evansville by the Servel company). Imagine how it must have felt to go from a dilapidated home without sewage service to one with a bedroom or two, a private bathroom, a coal/wood-burning stove, and a refrigerator.

I tour a lot of community history museums that are little more than a final resting place for items cleared out of ancestral homes—covered in dust and lacking curatorial vision. This one is not one of them. It places Evansville's Black history into three historical periods illustrated by displays and interactive features—including a Lego studio for kids.

A full history of Black life in Evansville is outside the limits of my newsletter, but The Indiana Historian, (available in full online) offers a tight summary. Dear to my heart is the fact that Evansville was home to the first free public library built north of the Ohio River exclusively for African Americans.

Perhaps you’re a person who might shy away from an African-American history museums and cultural centers, with concerns that it might be too painful or that the programs might produce feelings of shame. I felt two ways about the Black history I learned in Evansville. First, was admiration for people who persevered and even thrived under the American caste system.

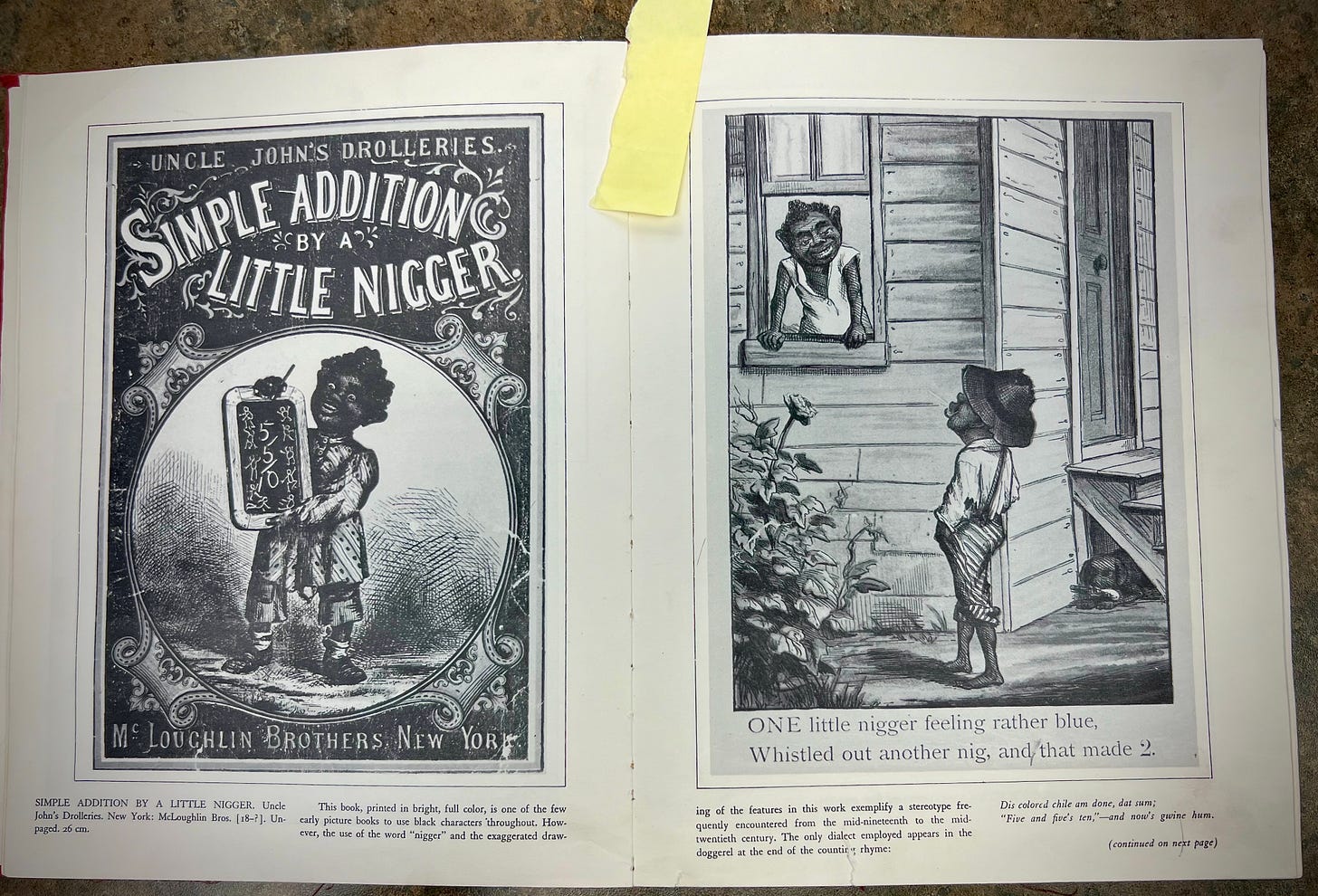

Second, I honestly found it painful to look at some exhibits, most notably a children’s counting book. Look closely at what’s inside and note the exaggerated features of the illustrated Black people and the profligate use of the N-word.

I am capable of feeling a lot of things simultaneously, including admiration and pain, as I felt in Evansville. There is a current debate about whether and how to teach Black history to schoolchildren and whether it might induce feelings of shame or result in outright psychological damage. I have been on a mission to educate myself on aspects of history that I wasn’t taught in school, and I’ve learned a lot of disturbing stories. I have never felt personally responsible for things I didn’t do, but I am responsible for holding myself and America to the standards we profess to ourselves and the rest of the world.

American history has shaped my worldview, character, and opportunities I’ve taken for granted. I regret that the history I learned in classrooms was incomplete. Evansville has opened my eyes a bit more widely to why we are the people we have become. I will make a point to visit Black history museums and cultural centers wherever I travel.

I invite you to share your experiences in Evansville, including visits to and memories of Baptisttown and Lincoln Gardens. If you know someone who might enjoy this, please pass it along.

Not only did Indiana’s original constitution limit the rights of Blacks, but the legislature kept making things worse for them. As late as 1851 Article XIII of the Indiana Constitution stated that, "No negro or mulatto shall come into, or settle in the State, after the adoption of this Constitution." Section 2 set fines for violations of the article, and Section 3 provided that money from fines be used to defray costs of sending Blacks in Indiana to Liberia. Earlier legislation required all Blacks already living in Indiana to register with the clerk of the circuit court. Learn more about Indiana’s constitutional restrictions on Blacks and half-Blacks at this link.

There is far more to know about the HOLC and its maps than I can cover here. I recommend reading The Color of Law: The Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America by Richard Rothstein and its companion, Just Action: How to Challenge Segregation Enacted Under the Color of Law.

Source. Also of interest to the 981 Project is the Transients Shelter (demolished) - Cairo IL. The Marine Hospital was located between 10th and 12th St., Cedar St. and Jefferson Ave. As part of Federal Project F-26: Improving Facilities for Sheltering Transients, the federal Civil Works Administration (CWA) rehabilitated the hospital in 1933-4 "as a shelter for whites and a two-story structure was put in shape to care for colored transients. The work involved the installation of heating and toilet facilities, painting, plastering, glazing, and general repair."

The legal scholar and author, Richard Rothstein, made this point in his book, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America