Behind the Smiling Face of "Midwest Nice"

Four books about the Midwest that blew my mind(set)

For those who missed an essential biographical note, I grew up in central Ohio—about thirty miles east of Columbus. Even though Ohio is the only Midwestern state I’ve ever called home, I have always identified as a Midwesterner, and have never called myself an Ohioan. Maybe that means I believe I epitomize the region: polite, farm-fed, and white.1 Oh, and nice. Above all, nice.

No matter where you live in the United States, you’ve probably internalized the idea that people in the Midwest are nice, like the American version of Canadians. Maybe that’s why so many Americans were shocked when a police officer murdered George Floyd in Minneapolis. What? In the Midwest? Where “nice” people live?

When I started The 981 Project, I had no idea that issues of race would continuously pop up in my research, even with the Ohio River being the longest slavery border in the country. And yet, even 150 years after the Civil War, that border history casts a long shadow into the present day. I grew up honestly believing that “racial issues” were something for Southerners to figure out, and wondered why they didn’t just get over it.

Aaron Kinard is a Ph.D. student in the department of sociology at the University of Virginia and author of an opinion piece in the Washington Post that explores the myth of Midwest Nice. It’s like he took a can opener to my cranium and stared into my brain:

Despite a deep and startling history of racism and the present-day reality of racial violence, the region has managed to avoid much scrutiny because of the myth that it is mostly white. Many white Midwesterners can live their lives with little or no interaction with Black people,2 failing to see the lack of racial diversity as a problem. This leads to some white Midwesterners constructing a narrative that “race is not a problem here.” Indeed, the “Midwestern nice” trope has helped some white Midwesterners see themselves as outside of the racist structures of our country…

When a town is nearly all white today, it can appear to its residents as natural, rather than an outcome that has been engineered and enforced over time. When white Midwesterners navigate their lives without interacting with Black neighbors, it becomes easy for them to believe that their predominantly white communities have no problems of racism—certainly not like the South.

With all that in mind, I’m sharing four books (of many) that have helped me understand things I took for granted about my region and racial indoctrination: Midwest Futures, A Fever in the Heartland, The Geography of Hate, and A History of Hate in Ohio. I hope one or more of them will interest you.

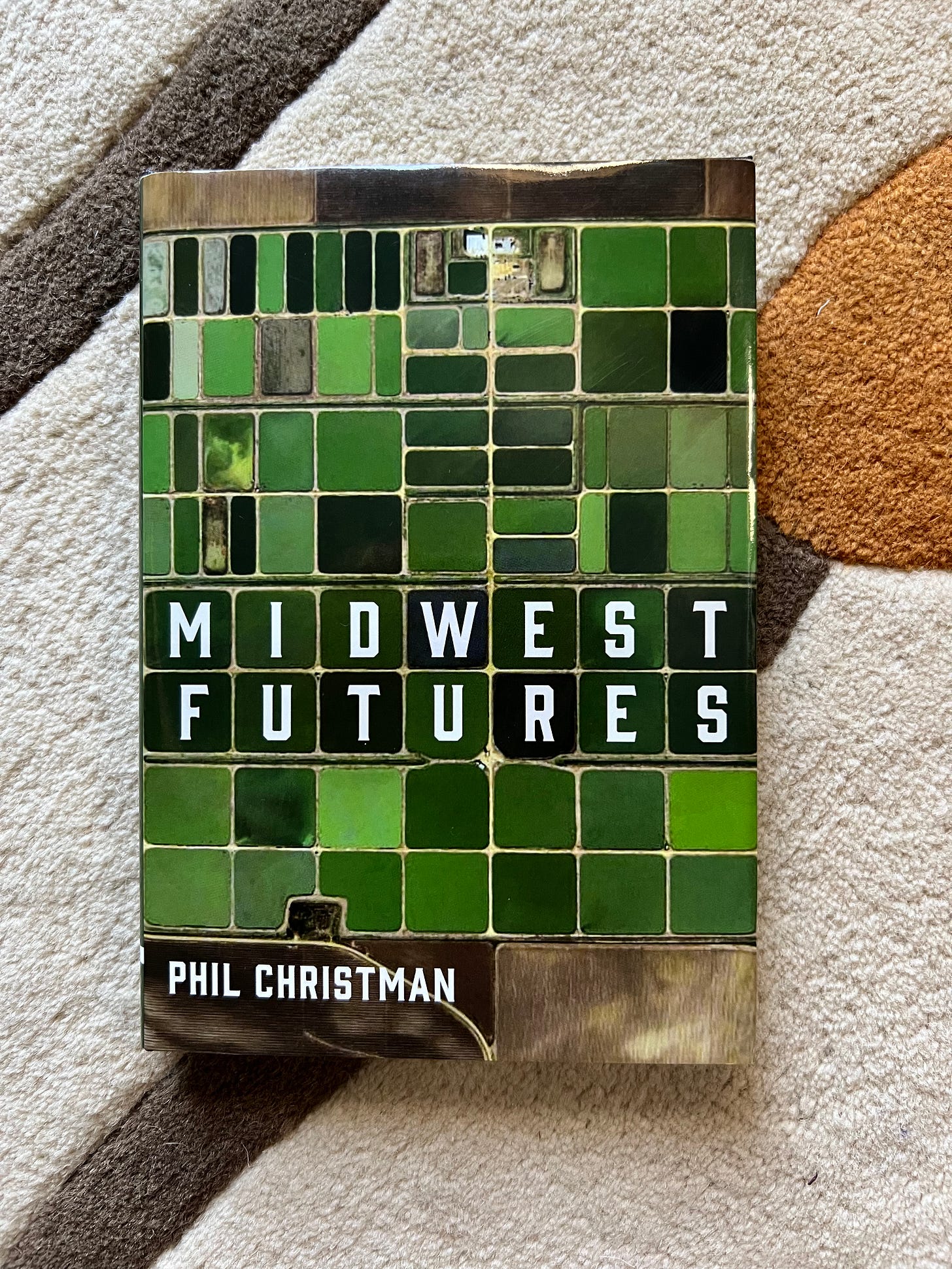

Midwest Futures

Phil Christman’s book sets the stage for a modern understanding of Midwestern identity. He starts by explaining that the surveyors who mapped the Northwest Territory into townships measured the land in the English style with six-foot lengths of chain. Each township comprised 36 boxes of approximately 6 miles per side. Christman uses this structure of 6x6 to offer a book of 36 essays of about 1000 words each. See how cleverly that’s reflected in the cover?

Despite this tidy organizing structure, the definition of the Midwest is downright messy. He points out that the old Northwest Territory is just the beginning of the Midwest, with parts of the Louisiana Purchase, the Ozark and Appalachia Plateaus, plus Union states, Confederate states, and one that couldn’t decide (Missouri) in the mix. In his words, it’s a “conceptual magpie’s nest, made from scraps of everything.”

What resonates with me is his observation that it’s “a kind of abandoned frontier,” both now and in the past. “You picture the whole region as a sort of once-shiny new mall marooned by suburban sprawl, left to crumble, only a few years after opening, in a no-longer-vital part of town.”

Christman’s experience of growing up without Black neighbors in Alma, Michigan, mirrors mine from Newark, Ohio: “Why would Black people, or anybody, want to live in Alma, Michigan? (I certainly didn’t.)”

Then he sets the record straight:

But a little historical digging reveals the truth: the Midwest has never been simply white, we’re a patchwork of disused Underground Railroad stations and former sundown towns, centers of Black brilliance (Detroit, Chicago, Kansas City) and centers of Klan revival (Indiana). Barack Obama grew up here. Philando Castile was shot here. That’s a history, even a vexed one.

With that, take a deep breath as I share three other books about the hatred (racial and otherwise) that lurks behind the smiling mask of Midwest Nice.

A Fever in the Heartland

Here’s a video with Timothy Egan, the author of A Fever in the Heartland: The Ku Klux Klan’s Plot to Take Over America, and the Woman Who Stopped Them. In it, Egan discusses why the second wave of the KKK convinced one in three Indiana men to place their hand on the Bible and vow to uphold white supremacy.

Egan uses the rise and fall of Indiana’s Grand Dragon, D. C. Stephenson, to illustrate why the Midwest was such fertile ground for hate and how 400,000 Hoosiers fell into the Klan’s clutches.

D.C. Stephenson was the ideal missionary. He had magnetism, unbridled energy, and a talent for bundling a set of grievances against immigrants, Jews, Roman Catholics, and Blacks into a simple unified pitch that made sense of a fast-changing America still dazed by the Great War…

The way to win over the Heartland was with a wholesome Klan, a Klan of family and faith and Midwestern values. It would not be the Klan of the whip and the sword, but the Klan of the hearth and the Lord…

All it took was a small bribe and a bit of Bible talk. The constituency was vast. Evansville alone had seventy-two Protestant churches. In short order (Stephenson) paid off a dozen or so ministers to evangelize on behalf of the Klan, spreading the word of hate along with the word of God. Those sermons were then widely reported in the Klan’s new Indiana weekly, the Fiery Cross. In Bloomington one Sunday morning, Reverend Vic Blair introduced Klan concepts to three hundred people in church while waving a copy of its constitution.

It seemed nothing would impede the Klan, which owned dozens of local, state, and federal lawmakers and jurists. Four governors were Klan members, including Indiana’s. The Klan’s ambitious legislative agenda included:

A new eugenics law to prevent parents with “degenerate hereditary qualities” from having children

Abolishing parochial schools and jailing parents who sent their children to them

Criminal penalties for adultery or sex outside of marriage

Prohibiting Sunday baseball games

State censorship of movies

Mandatory Bible readings in public schools (only from the King James version that Protestants preferred)

One woman finally got in the Klan’s way, and she gave her life in the doing. Madge Oberholtzer was one of many women that Stephenson abducted and raped, but she was the only one to give a deathbed testimony that resulted in his murder conviction. It’s a grisly tale.

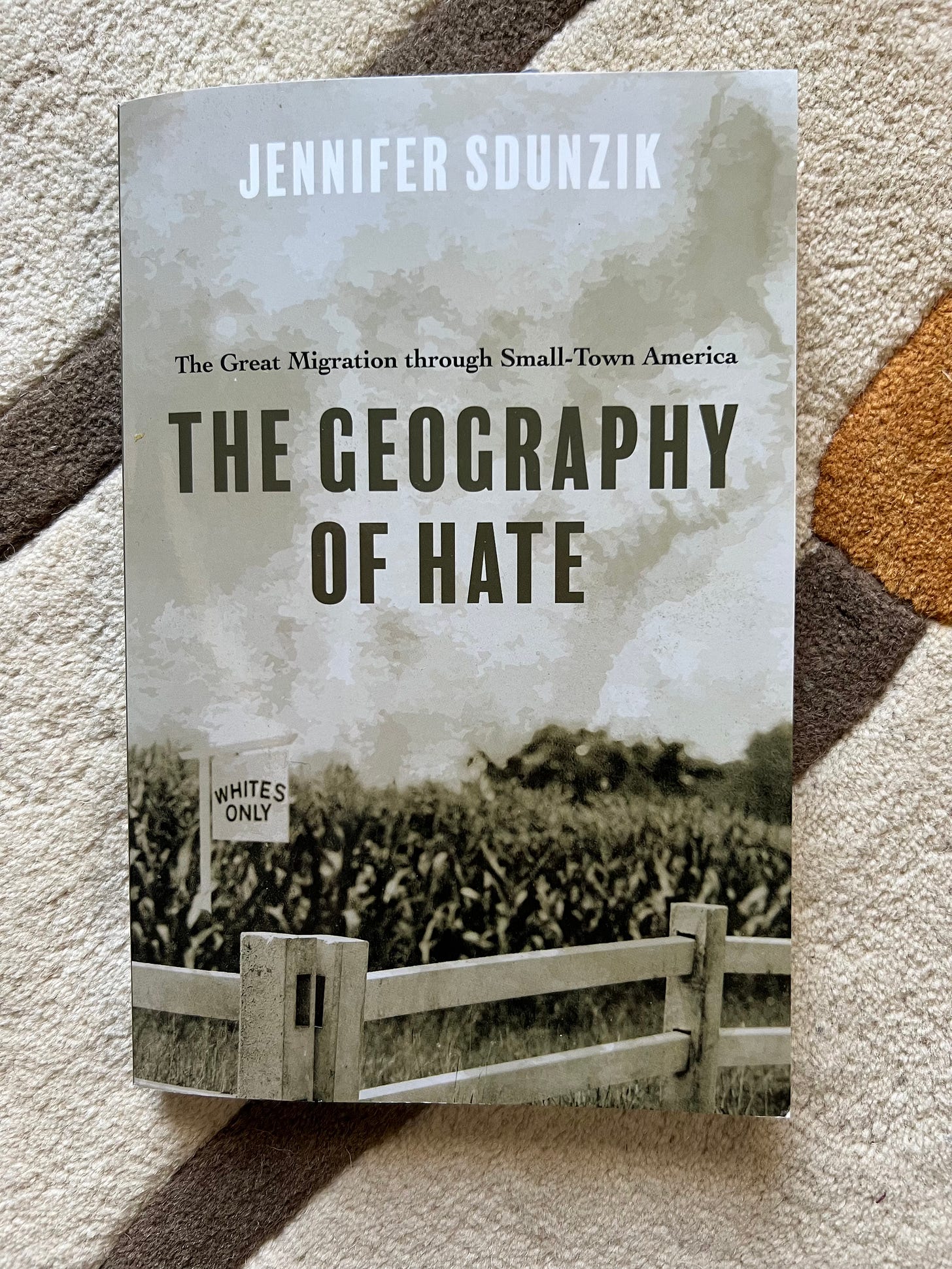

The Geography of Hate: The Great Migration through Small-Town America

Once again, Indiana comes under scrutiny in this book by a postdoctoral research associate at Purdue University, Jennifer Sdunzik. She examines how, during the Great Migration, conscious and unconscious white actions all but erased Black Americans from the state. She doesn’t ignore other Midwestern states, but her focus is Indiana.

For context, the Great Migration took place in two waves. The first began in 1915 after the start of the Great War and lasted until the Great Depression. In 1920, Indiana was 95 percent native born, and 97 percent white. The massive influx of Blacks made European Americans see themselves as one people, regardless of ethnic distinctions.

The second wave started at the end of War War II and was the larger of the two, with about 5 million Black Americans looking for a better life outside the South.

The author challenges common-held knowledge that Blacks preferred urban centers over rural or suburban options. She shows how white socioeconomic anxiety resulted in an increase in sundown policies3 that kept them out. Formal history texts excluded these tactics, and the public avoided discussing them, allowing people from Midwestern towns (like mine) “free to reimagine its past and commemorate moments of pride, such as being a stop on the Underground Railroad, without reflecting on the policies and attitudes that prevented Black southerners from staying and settling in their towns.”

Ouch. I grew up twenty miles from a supposed Underground Railroad stop. I hate to admit this, but I never considered why small towns and farming communities didn’t attract large numbers of Black migrants, who were familiar with agricultural work.

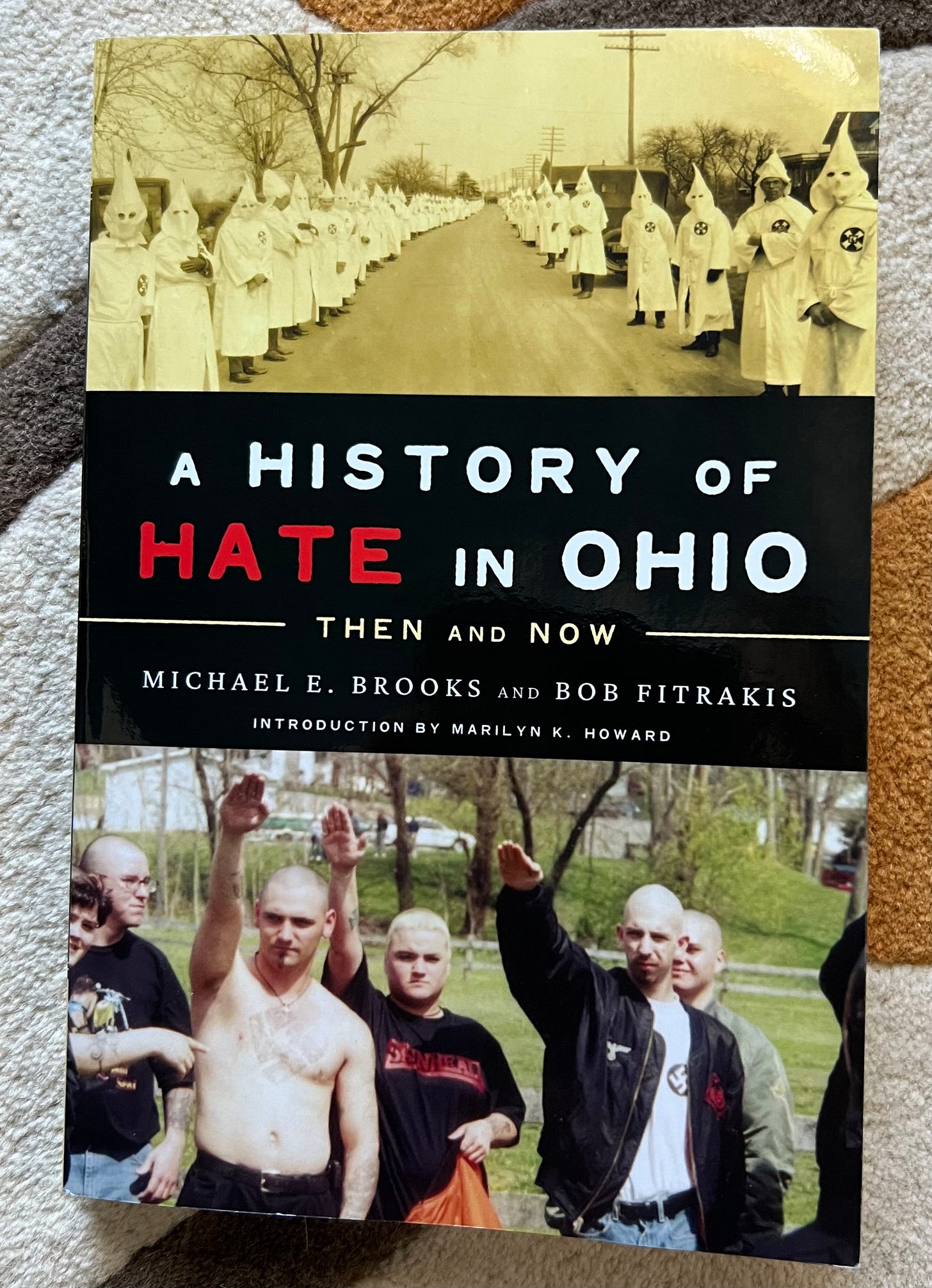

A History of Hate in Ohio: Then and Now

I may not have learned Ohio’s racial history in school, but this book, by a historian and a journalist, lays it all out—with photos and footnotes. The opening paragraph of Chapter One is ripped from my subconscious:

There is a present-day tendency among the general public in the states that remained part of the Union during the Civil War that the North was somehow immune to the malignant racism that underlay the institution of slavery that emerged in the American South…This is particularly the case with many white Ohioans, who learn a rosy, sanitized version of their state’s history in fourth grade. After all (or so goes this view), no state had greater participation in the Underground Railroad, and many of the leading American abolitionists at one point called Ohio home.

The book is presented in two parts, historical and current. Part One is by Michael E. Brooks, a professor at Bowling Green State University. It tells me everything we should have learned in public schools and universities, including:

White Ohioans exhibited “extreme hostility to Blacks living in the state” from the earliest days of statehood (1803). Many of the first Ohioans came from states where slavery was legal, so one of the first legislative acts in the state were measures designed to “regulate Black and mulatto persons and/or escaped enslaved persons.” These were called Black Laws and carried penalties for aiding, harboring, or employing an escaped slave. In 1807 the legislature raised the stakes for Blacks and whites considerably.

The first public school acts of 1821 and 1825 didn’t use race as a qualifier for access to schools, but in 1829, the act was clarified, “nothing in this act contained shall be so construed as to permit Black or mulatto persons to attend the schools hereby established…”

Part Two is written by Bob Fitrakis, a professor of Political Science at Columbus State Community College and editor/publisher of the Free Press. He carries the narrative from 1970 to the present day. I had forgotten that it was an Ohio man, James Alex Fields Jr., who drove his car into a crowd of counter-protestors at the “Unite the Right Rally” in Charlottesville, Virginia, killing one woman and injuring dozens in 2017. He was sentenced to life in prison for his crimes.4

I appreciate how Fitrakis calls out mainstream institutions, including The Columbus Dispatch, for ignoring and downplaying hate crimes. It goes without saying that politicians and civic boosters do, and did, the same.

Thanks for joining me on this journey of self-discovery and reflection. I welcome all civil comments and any books, websites, or other resources that will help us all heal our fractured hearts and nation.

See you in a couple of weeks with April Trivia!

In contrast I married a man who thinks of himself as a Virginian. Sure, that makes him a Southerner, but unlike me, he identifies with his state instead of his region. Why is this? I’ll let you know when I figure it out.

I never shared a classroom with a Black student until I entered college.

You might be familiar with sundown towns if you watched the movie The Green Book. I haven’t yet read Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism, a 2018 book by sociologist James W. Loewen. Having grown up in Illinois, he anticipated finding maybe 10 sundown towns in Illinois and 50 across the nation. He had no idea. As of 2020, the best estimate for Illinois alone was a bit more than 500, which is 70% of all towns in the state. Similar proportions of towns in Oregon, Indiana, and other Northern states also went sundown, mostly between 1890 and 1940.

At his plea hearing on March 27, 2019, Fields admitted under oath that he drove into the crowd of counter-protestors because of the actual and perceived race, color, national origin, and religion of its members. He further admitted that his actions killed Heather Heyer, and that he intended to kill the other victims he struck and injured with his car in the crowd. Source.